Category: open standards

Doctor, doctor …

A MP stumbles, coughing, into the doctor’s surgery. There is blood pouring from the ears and nose and left eye. “Doctor, doctor, I’ve just had a bad fall and I think I’ve broken my wrist” gasps the MP. The doctor has a look and briefly feels the pulse. “Does that hurt?” “A little bit” mumbles the MP. “I don’t think it’s that bad” says the doctor. Unfortunately I can’t check it today as the digital X-ray machine is broken”. The MP is swaying back and forth. “It’s probably just a bruise, the nurse will give you a sling. Take it easy for a couple of days and come back if it’s still painful.” The MP staggers out of the surgery, still bleeding from the ears, nose and eye. The doctor is already focused on the file of the next patient, because doctors are very busy.

The process described above resembles the way the Court of Audit went about answering MPs questions about our national IT strategy. The MPs asking those questions were not experts and the Court provided simplistic answers without providing any context or stopping to consider whether the symptoms might be part of a broader problem. The newly-published report failed to respond even to the superficial questions and, moreover, based its answers on minimal data. Which is a disgrace, as it is precisely the role of the Court to delve into the deeper issues.

Instead of focusing on the 88 million euros spent on licence fees (less than 1% of the total annual licence expenditure), the Court could and should have explored why a different approach can work in other European countries, but fails in the Netherlands. Is this country really so different from Finland, Germany, France or Spain? As their colleagues in the Central Planning Bureau had done in 2009, the Court could have produced its own qualitative analysis of the macro-economic effects of large-scale, open source implementations. This as a viable alternative to annual imports totalling of more than 8 billion, primarily from the USA. The macro-economic demand alone is relevant since the VAT and profit tax of this trade ends up predominantly in the Irish treasury, because of inter-EU trade regulations. (I ‘m not necessarily against bailing out Ireland but this can surely be done more efficiently). Also the figures of the 2004 SEO study are still current enough to be indicative for order of magnitude estimates.

As one of the ‘experts’ consulted by the Court, I am very disappointed by the minimalist approach it took. But perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised – after all, in a previous report, the Court had also dithered, even after they had determined the government really had no insight whatsoever into its own IT spending. It is beyond me why a subject such as IT, where so many aspects can go so terribly wrong, is not more thoroughly and strategically overseen. In my written input to the Court last year I proposed several clear ways to frame the fundamental questions. For those who, like doctors, are very busy here is a summary:

Dear MPs, the Netherlands is a modern western country with access to the same knowledge, technology and IT budgets as Germany, France, Spain and Finland. Today all these countries have already achieved widespread adoption of open source and open standards in government. The work of the Dutch government is also very similar to these countries – certainly generic aspects such as office automation. So, eight years after the original and unanimous vote by parliament, surely the only reason that the Netherlands cannot implement this policy is our administrative culture and our Atlanticist political orientation. There is certainly no fundamental reason why the results of the other countries I mentioned cannot be replicated in the Netherlands, particularly because those same countries have already done all the preliminary research for us. But in recent years potential obstacles for migration have been elevated to norms, rather than being correctly identified merely as part of a problem to be solved.

Parliament should no longer accept high dependence on a supplier being invoked as an excuse for not making progress towards becoming less dependent on that supplier (as the government did in response to parliamentary questions in in 2004, 2006 and 2008). The high dependency is the problem that must be solved, not an immutable law of nature where IT departments are the powerless victims.

Parliament should no longer accept the acknowledged lack of technical and organisational expertise of the 60,000 government IT professionals (and its suppliers) as a valid excuse for the lack of progress. It is implausible that the Dutch state cannot find the requisite skills to replicate the results of its European neighbours. Any IT staff and management found lacking in the necessary skills to carry out the very reasonable requests from parliament should be retrained or replaced. Incompetence is grounds for dismissal, not a valid excuse to refuse to do the work.

Of course there will be problems in unravelling this gigantic Gordian knot, created by decades of accumulated proprietary software. But the most frequently cited excuses for not making a start with OSS and OS are similar to those used by asbestos manufacturers: "yes, but it is handy", "we have been using it for so long", "we are comfortable with it", "we know nothing else". All factually correct statements, of course, but certainly not valid excuses to prevent us from finding an alternative solution.

If the government had started making these changes way back in 2002, as parliament voted to do, the cutbacks we’re now suffering in education and health care would have been more than covered.

On this issue, the Netherlands seems to have been reduced to providing the frightening role for the rest of Europe on “how not to do it….”. Too bad.

Asbestos is also useful

For decades throughout the Western world houses were built with asbestos. The material is affordable, durable, insulating and also has excellent fire resistant properties. All this – and the low price – made it the ideal stuff to use for everything. Which is what we did.

For decades throughout the Western world houses were built with asbestos. The material is affordable, durable, insulating and also has excellent fire resistant properties. All this – and the low price – made it the ideal stuff to use for everything. Which is what we did.

As long as the asbestos remains safely in place, nothing much happens. It does its job and you don’t need to think about it. The problems begin when changes are made, such as a conversion. The demolition of a such a wall releases microscopic asbestos fibres, resulting in enormous danger to the health of anyone who has the misfortune to be nearby. Consequently the processing of asbestos is very strictly regulated. Despite these regulations, asbestos has for decades caused twice as many deaths as road accidents.

Because the long-term consequences of the use of asbestos is so damaging, its use is now prohibited. All this, despite the fact that the original reasons for using still exist: asbestos is still cheap, strong, durable, insulating and fire resistant. Yet we now don’t use it because the social price is just too high. Strategic and social reasons are more important than practical and technical advantages.

Yet when we talk about the software that governments use for their daily work, it seems virtually impossible to distinguish between strategic and operational arguments. Concerns about the fundamental inadequacy of closed (and uncontrollable) systems are easily dismissed by phrases such as "it’s useful", and "everyone’s used to it”, or even “political concerns are not up for discussion”. All these quotes were also used by asbestos suppliers in the 1980s.

Fortunately, the traditionally cuddly but now dangerously naive Dutch approach to international relations was brutally interrupted last month: the Dutch government has been lying to itself and us about military deployment; people’s cloud-computing data is indeed vulnerable; Israel and the USA use their technical knowledge of proprietary systems to attack their digital adversaries; and 10% of Dutch PCs have been taken over by criminals. The latter is a direct consequence of the desktop-monopoly actively created by the government, and to this day strengthened through its IT-education policy.

Today it’s an Iranian nuclear installation, the personal data of Rop Gongrijp, and the domain of Wikileaks. Tomorrow perhaps it will be a Dutch (air)port, power station, hospital or a few ministries?

If the Netherlands wishes to retain control of its own sovereignty, we have to stop this quasi-naivety in conversations about technology strategy. Despite all international agreements, the law of the jungle still prevails, but we behave like we’re taking a stroll in the park. NOiV (or its successor programme) must find the courage to start a conversation about the strategic implications of running our public administration on systems that are not under our control. It is time to strictly regulate our public sector asbestos-information. Although it can be useful, we must seek out alternatives that ware safe for everybody.

Parliament’s questions to the Court of Audit

Preamble

Preamble

The Lower House of the Dutch Parliament has asked the Court of Audit to investigate the problems and opportunities related to the adoption of open standards and open source software for the government’s information systems. The Court has invited various experts to give their views. This blog post is my contribution.

The questions are being asked to the highest supervisory body of the country, rather than the departments responsible for implementing this policy – the Ministries of Home Affairs, and also Economic Affairs, Agriculture & Innovation – eight years after the government’s first unanimous vote on this issue and the expenditure of about 5 billion euros on licensing fees. The impression given to the outside world is that Parliament is not impressed with the progress of the last eight years and believes that the relevant government departments could benefit from the external scrutiny of a neutral and objective body.

Each of the following five questions implies a series of unspoken assumptions. In order to answer the questions, it is necessary to identify and, where neccesary, challenge these underlying assumptions in order to reach a sensible answer.

The five questions

Here are the answers to the questions raised by Parliament. There is so much interdependence that subsequent responses will sometimes refer back to earlier parts.

“You cannot solve a problem with the same thinking that created it”

1.What possibilities and scenarios exist for the reduction of closed standards and the introduction of open source software by the central government (ministries and related agencies) and local authorities?

The Netherlands is a modern western country and has the same access to knowledge, skills, technology and comparable budgets for IT as Germany, France, Spain and Finland. It is a fact that all these countries have already implemented large-scale adoptions of open source and open standards in government. The implementation requirements of the Dutch government are also very similar to these countries. The reason that The Netherlands has not moved further in this area, eight years after the original, unanimous Parliamentary vote, can therefore be attributed to nothing more than the administrative culture and our Atlanticist political orientation.

There is no fundamental reason why the achievements of these other countries cannot be replicated in The Netherlands, especially as the groundwork has already been done. Barriers to migration have often been treated as immutable laws of nature rather than just a problem to be solved.

- Parliament should no longer accept that a high dependence on one supplier is an adequate excuse not to move away from that very dependency (as the Cabinet did in response to parliamentary questions in 2004 and 2006 and 2008). The dependency itself is the problem that must be addressed, not an enshrined principle that IT departments must endure.

- Parliament should no longer accept that the acknowledged lack of technical or organisational knowledge amongst the 60,000 government IT professionals (and their suppliers) is an excuse for the lack of progress. It is implausible that the Dutch government is incapable of replicating the successful work of its European counterparts. Any governmental IT or management staff who do not have the requisite skills to carry out the very reasonable requests of Parliament should be replaced or retrained. Incompetence is grounds for dismissal, certainly not an excuse for refusal to do the necessary work.

- Intrinsic motivation works better than coercion. Administrators and IT staff who understand the wishes of Parliament can embrace it with real conviction and are likely to want to produce better results than those who only work under duress. Such an approach will select and promote suitable people to the right jobs. The staff whose policies and behaviour have caused our current problems are probably not going to the ones who find the necessary solutions.

- The link between HR and remuneration policies for IT professionals and achieving technical certification related to proprietary software from a handful of suppliers must be completely severed.

“When you find yourself in a hole, stop digging”

2. What part of closed standards and software can be replaced by open standards and open source solutions and what cannot?

This question has yet another unspoken assumption: that central government has a realistic oversight of all systems, applications and related standards. It does not. As a result, questions about the number of systems that can be replaced are very hard to answer and have little relevance to achieving lower costs and greater independence in the foreseeable future – primarily because of the very large differences in costs that are associated with different standards. The government would do well to focus on the most common, generic issues, for which proven alternatives already exist. The original 2002 Vendrik Parliamentary motion already asked for this.

Key points to identify: what are the most expensive closed source areas where functional open source alternatives already exist and are already being used successfully elsewhere? What are the closest functioning areas that can result in successful migrations?

Migration plans should be drawn up in these areas as a matter of high priority – and this means halting or delaying other projects that may block these migrations and accelerating projects that play a supporting role.

For instance, in 2005 the former Ministry of Economic Affairs produced a document management system which has made it virtually impossible for years for the Ministry to use other web browsers, word processors or desktop operating systems. This is particularly surprising as, in 2004, the government itself announced that such closed systems in the work environement were harmful and undesirable, and were therefore going to be actively addressed as per the wishes of Parliament.

A current, concrete example within national government is the introduction of SharePoint. There is a significant risk that this investment, once made, will be (ab)used yet again as an excuse not to migrate to open and available alternatives. That would take us up to 2016 (14 years after the initial Parliamentary decision!) before any real work could begin on migration.

“Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.”

3.What are the current costs? What are the predicted up-front and structural costs costs of moving from closed standards and the introduction of open source software? What are the projected savings?

The Dutch government currently spends about one billion Euros on proprietary software licences annually. These licences are mainly foreign, and the income tax and VAT on this expenditure flows into the Irish exchequer, because most European branches of American software companies are based there. The total Dutch expenditure is eight times more. Both governmental and general software expenses grow by about 10% per annum and are therefore unsustainable.

The Dutch government currently spends about one billion Euros on proprietary software licences annually. These licences are mainly foreign, and the income tax and VAT on this expenditure flows into the Irish exchequer, because most European branches of American software companies are based there. The total Dutch expenditure is eight times more. Both governmental and general software expenses grow by about 10% per annum and are therefore unsustainable.

A significant portion of these annual costs can be saved or ploughed back into the local economy through Dutch SMEs, and so this cost will be an investment in the Dutch knowledge economy. With the government as the leading customer in this new market structure, it is feasible that The Netherlands could save billions per year.

In addition to these direct costs, various indirect savings could increase this amount many times over: the costs of management and security for vulnerable mono-cultures; the cost of merging old legacy systems and new applications; and social costs caused by security failures and easily avoidable software security problems. Every month there are Dutch hospitals whose primary processes are severely disrupted by computer viruses – a direct result of monoculture.

Moving beyond the financial, it becomes more difficult to quantify the social impact of the high dependency level of Dutch society on certain foreign, privately-owned companies. However, if more than 80% of the PCs in The Netherlands can be remotely controlled or even switched off, what does that say about Dutch national sovereignty? Is it politically acceptable for foreign software suppliers or government bodies to have an On/Off switch for ministries, municipalities, police, hospitals, water works, supermarkets, schools etc…?

“The best moment to plant a tree is 25 years ago, the next best moment is now.”

4.How would the reduction of closed standards and the introduction of open source software be realised?

With not only the right mandate (which Parliament actually voted for eight years ago!), but also the right expertise significant results are attainable within 24-36 months. This requires making this area a priority issue and a break from the old attitudes, excuses and methodologies of recent years (see answer to question 1). Successes abroad can serve as templates for our projects.

One area where we could make a rapid start would be primary education. Currently we are actively strengthening existing monopolies via this sector with public money. If by 2011/12 the first two years of primary school use open systems and then a higher class is switched each year, The Netherlands will have the first generation of citizens who are trained in vendor-neutral systems entering the workforce in 12 years, easily capable of working with multiple systems and applications. De ‘Rosa Boekdrukker’ primary school in Amsterdam clearly shows how this can be done.

Dutch hospitals in The Netherlands could follow the example of the Antonius Hospital in Nieuwegein. Many other hospitals can share in this success. And because it’s already been shown to work, the risks and costs for the next 100 hospitals are much lower.

It will take at least a decade before the full potential of open source and open standards can be utilised.

“Go out on the limb, that’s where the fruit is”

5. Beyond the cost, what other advantages, disadvantages, risks and opportunities should the Court of Audit factor in? What conditions must be met to make possible the implementation of open standards and open source software?

Benefits & Opportunities

- Savings of billions per year in direct costs for all citizens and IT-using organisations in The Netherlands.

- Redirecting a stream of funds from Ireland / USA into Dutch society as a huge and permanent investment in our knowledge economy.

- Government investment in software will result in free, reusable software and knowledge available to our whole society, rather than controlled by privately-owned and usually foreign companies.

- Security is strengthened through greater diversity of IT, competition, and the possibility of custom code audits.

- National sovereignty is reinforced when the government has complete control over its systems.

- General IT competence will dramatically improve, ensuring fewer spectacular and expensive failures such as the 2006 ‘Walvis’ Tax project, national medical records, public transit chip cards and, most recently, the new police system to name but a few.

Disadvantages and risks

- The current, fragmented IT policy of the Dutch government means that a thousand little fiefdoms may need to be broken up.

- The apparent lack of skills amongst IT management may have consequences for personnel. No doubt there will be resistance.

- Significant investment is probably needed in re-training government IT professionals.

- Angry phone calls from Washington DC when the flow of licensing money is shut off.

Preconditions

- See answers to question 1.

- Be realistic about the positioning and motivation of software companies. Companies seek to maximise profits, control markets and will therefore exploit any leeway that the government offers them. We do not invite the turkey to discuss the Christmas dinner. Therefore why do we accept “advice” from software companies and their interest groups about the best software strategy?

- We need to break away from the idea that extensive outsourcing is necessary, effective or desirable. The raison d’etre of government is to justly serve the legitimate needs of its citizens; it should therefore have detailed and inherent control over information systems. Stop the corporate-speak and ‘playing business’ by civil servants. Government is not a business, nor should it pretend to be. Outsourcing the control of information processing systems is contrary to the very principles of a democratic state for exactly the same reasons that outsourcing the military forces or the judiciary would be.

- Make a clear distinction between political and administrative goals and the means of achieving them. Cutting costs can be realised in many ways, regaining national sovereignty in only one.

- As long as desktop projects implemented under the guise of “efficiency through economy-of-scale” result in each desktop costing 6600,- Euros per annum, this kind of bullshit-bingo is completely risible. Keep IT managers and other decision makers who don’t know the difference between desktop-standards and a "standard-desktop" away from such projects.

Cloud computing, from the frying pan into the fire

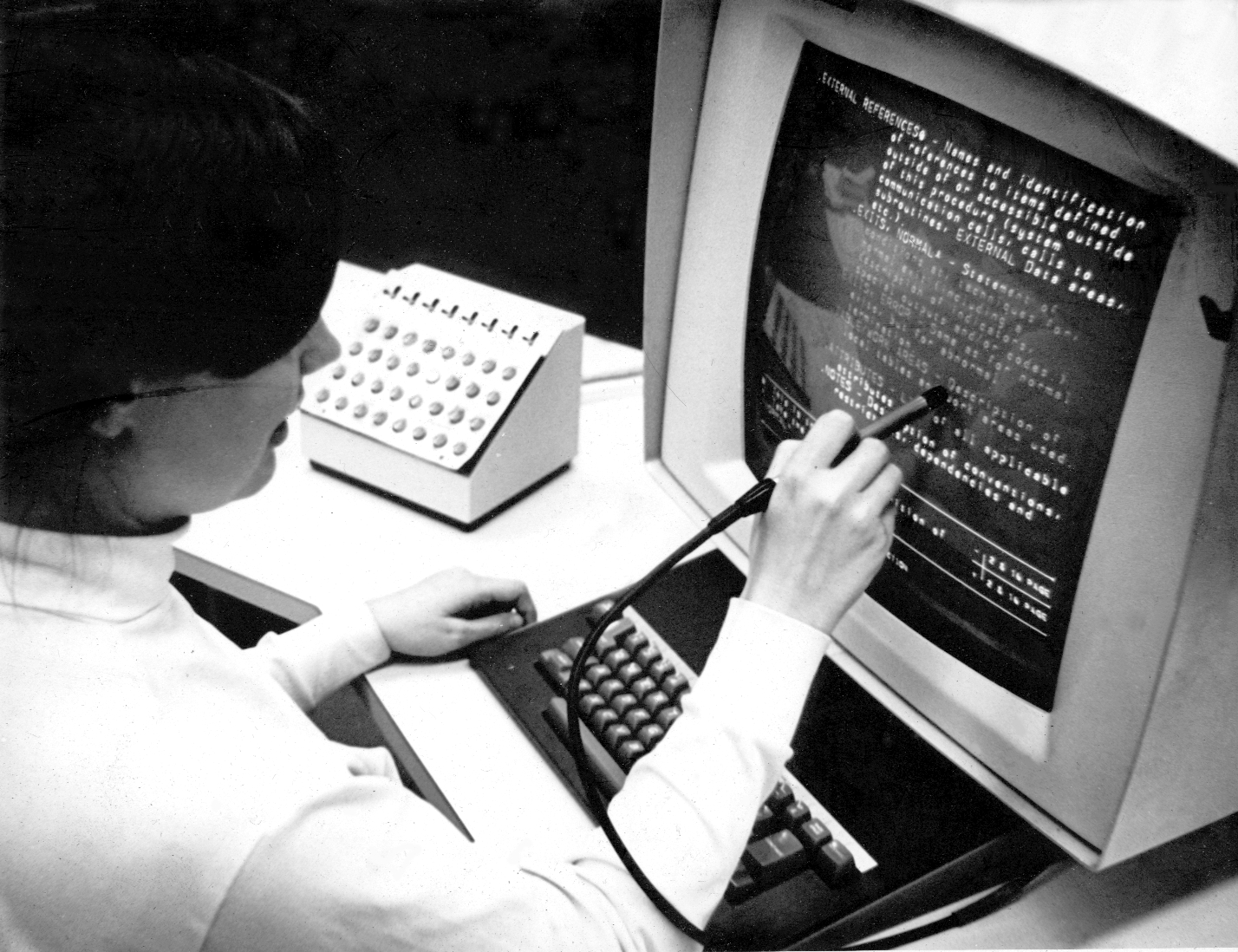

In a recent column (Dutch), Frank Benneker of Amsterdam University explored the consequences of the rapidly growing use of cloud computing. The shift of computer applications from PCs and servers to a single "service" provided through a worldwide network is probably as fundamental a shift as the earlier one from mainframe computing to PCs.

In a recent column (Dutch), Frank Benneker of Amsterdam University explored the consequences of the rapidly growing use of cloud computing. The shift of computer applications from PCs and servers to a single "service" provided through a worldwide network is probably as fundamental a shift as the earlier one from mainframe computing to PCs.

Given the objectives of the Dutch Open standards and interoperability policy plan, cloud computing seems the quick and easy-to-implement solution: I hear Web 2.0 enthusiasts say “put everything on Google Docs and we are all interoperable”. But just as in the case of the "liberation" of PCs from mainframe managers/suppliers, there are problems with cloud computing – potential snakes in the grass.

In December 2004 the Dutch government decided that the dependency on dominant software providers was a problem and had to be addressed. The Dutch action plan from 2007 was the first, tentative step in dealing with this.

The Dutch government wants to use open standards for interoperability, and open source to foster independence, lower costs and strengthen local development (services instead of licences). Open standards are fundamentally essential for interoperability. The Dutch ‘standard’ government desktop plan demonstrates to governments that interoperability can also be achieved with an imposed, top-down mono-culture. Give everyone the same software, and information can be conveniently exchanged.

However, the price of a mono-culture is high, both directly in money and in less quantifiable aspects such as security problems and an extreme dependence on a few foreign private companies. The latter is especially difficult to reconcile with the idea of a sovereign nation and a government that is democratically accountable. Surely our governments would wish to avoid relying on foreign companies to control the connectivity of our information databases in some nebulous “computer cloud”?

The crucial point is that even in this cloud, the hardware does not belong to the government nor is it possibly even on Dutch soil. The hardware can be located anywhere in the world, and therefore subject to multiple legal regimes beyond the Dutch government’s control (or indeed, accountability).

Much of the Web 2.0 knowledge for the Dutch government and discussions about this are held on ning.com servers, and the consensus is that it would be pretty difficult to migrate away from there. Even NOiV, the Dutch open standards and opensource implementation bureau also holds regular discussions on LinkedIn instead of its own XWiki environment. It is only natural that people use what they know. However, bearing in mind not only the objectives of the Policy Document, but also the various Parliamentary Motions on the subject and the earlier decisions of the government itself, cloud computing is a major IT problem. To expect cloud computing to rid us of the issue of “lock-in” that has been a problem for the last 20 years creates a classic example of ‘out of the frying pan; into the fire ‘.

Our current problems arise from not foreseeing the long-term consequences of our IT choices. We need a separate government IT programme to ensure the freedom of choice that we see as entirely natural in other markets. Unless the cloud computing servers are on Dutch soil and we have access to the code under an open source licence, we shall only go from bad to worse.

The Free Software Foundation has the solution for these problems, a distributed cloud that we can all access. Servers that provide free software designed to guarantee our digital freedom. After all, this is the original intention of the Internet: all equal players in their own cloud.

Kroes: vendor lock-in a waste of money

In a recent speech EU Commissioner Neelie Kroes stated that badly functioning IT markets and high vendor dependence have far-reaching consequences for the functioning of public bodies and companies in Europe. There is much to be gained, both economically and functionally, by focusing on open standards and open source software. ‘This is a waste of public funds no government can afford any longer.’

In a recent speech EU Commissioner Neelie Kroes stated that badly functioning IT markets and high vendor dependence have far-reaching consequences for the functioning of public bodies and companies in Europe. There is much to be gained, both economically and functionally, by focusing on open standards and open source software. ‘This is a waste of public funds no government can afford any longer.’

The Dutch IT magazine Computable.nl has a summary of the speech with my comments (original in Dutch – Google translation here). English commentary on the speech here, here and here.

Autoimmune disease in the pig pen

Computer viruses and palliatives against them are a growing threat to high-tech care. There is a classic solution for the old problem of a vulnerable mono-culture: diversity.

Computer viruses and palliatives against them are a growing threat to high-tech care. There is a classic solution for the old problem of a vulnerable mono-culture: diversity.

Last Monday alarm bells went off in many IT departments. A viral infection on Windows XP computers was initially caused by an anti-virus update from McAfee. The update made part of the system appear to be a threat and system file protection software made the system unusable, a type of auto-immune disease.

In hospitals and care institutions XP is still widely used, as specialised medical applications are often not ready for the new Windows version (and as often purely because of under-investment). This time it was McAfee, but almost all anti-virus products from time to time cause such problems. Anti-virus updates are a real-time arms race and sometimes in the rush things goes wrong.

From agriculture and ecology, we know that monocultures are efficient but also very vulnerable. It is no different in the pig pen of IT. The management of 4500 identical systems seems simpler than a more varied infrastructure – until a virus or autoimmune disease outbreak. Then the overtime starts. The scale of many of these incidents shows that even large health care institutions do not have proper internal firewalling and compartmentalisation. Nevertheless, the situation is better than five years ago.

Security issues caused by monocultures are not a new story. In 2003 Daniel Greer and Bruce Schneier wrote a report about the security implications of the dominant OS monopoly. Since that time neither the market nor the government has succeeded in effectively breaking this monopoly. In health care applications with medical or laboratory equipment included, many are Windows-only. Vendors often set additional conditions on the PCs, for example no firewall, before guaranteeing proper functionality for of their own applications. Thus a computer virus (or an autoimmune disease) is not only annoying for the admin department, but can also make scanners unusable. The MRI scanner can still take images, but the PC is crucial to the operation and viewing the results. So a Philips or Siemens unit worth a cool million is effectively scrap metal and patients cannot be treated. Sooner or later, this is a real time problem and then way more people than just the help desk are affected. In England, more than 1100 National Health Service computers were infected with a data-thieving worm. And there goes your medical confidentiality.

From the many conversations I have had in recent years with IT workers, I conclude that the difference between a product monoculture (a ‘standard’ desktop) and the application of standards to achieve interoperability is still not understood. Some years ago I spoke to a ministry official who enthusiastically told me that a ‘standard’ desktop was going to be implemented for the entire government. When I asked what standards would be applied, he launched into a list of products, "this version of an OS, this version of a word processor" and so on. The perception is prevalent amongst many IT managers that systems can only work and be properly managed if they are all from the same vendor and version. But this is much more a symptom of market failures and the immaturity of the IT industry. It is a problem to be solved, not a law of nature to which we have to adapt.

That there is another way to do things can be seen from the work over the past 10 years in the Antonius Hospital in Nieuwegein. There they have consistently, in small steps, consciously worked to minimize dependence on a particular vendor, platform or application. What most IT managers of health institutions describe as ‘impossible’ has been done in Nieuwegein. Fortunately this hospital is in the centre of the Netherlands so when a really big crash occurs all critical patients can be sent there. In 2010 we can avoid succumbing to the first virus or software-update-gone-wrong by using virtualisation, web-enabling and open standards environments to build greater diversity and interoperability.

Documents… differently

(Dutch column voor ‘digital government’)

What is a document? It started as a flat piece of beaten clay, onto which characters were scratched with a stick. 8000 years later it was found and after years of study, archaeologists concluded that it said: ‘You owe me three goats”. ??

What is a document? It started as a flat piece of beaten clay, onto which characters were scratched with a stick. 8000 years later it was found and after years of study, archaeologists concluded that it said: ‘You owe me three goats”. ??

Through papyrus and parchment scrolls we arrived at mass production of paper and book printing in Europe in the 15th century. Our sense of the nature of a document is still derived from this previous revolution in information capture and distribution. When computers became commonplace as a tool to create documents, there was therefore a strong focus on applications to produce paper document as quickly and nicely as possible. The creation had become digital, but the final result was not fundamentally different from the first printed book in 1452.

Most word processors in use today cling to this concept. There are hundreds of functions for page numbering, footnotes and layout to achieve a legible final result – on paper. Many IT tools around the management and access of documents are directed to the concept of a digital document as a stack of paper. Ready to print for ‘real’ use. The modern ways of working together for various reasons no longer apply to a paper-oriented way of recording and distribution. Paper is static, local, and now much slower and more expensive to transport than bits. It is this combination of restrictions has led to new ways of creating documents where both the creative process and the end result is digital. A famous example is Wikipedia, the world’s largest encyclopaedia with millions of participants continually writing and rewriting about the latest insights in technology, science, history, culture or even the biography of Andre Hazes.??

In this new form a document is a compilation of information at an agreed place online. In Wiki environments anyone can register and then comment or improve the document. This input is visible and therefore usable for all other participants so the end result is the sum of knowledge rather than the interpretations of a small number of "editors". ??

If the future of documents is digital, with a new way of working we also need new tools. Page numbering and footnotes are irrelevant in hypertext. However, what is relevant in a culture of transparency and collaboration is software that allows comfortable "writing" (another old word) in a web browser.

Nederlands

Nederlands

English

English